Dr.

Merton L. Root

pioneered the Science of Biomechanics to the podiatric profession and established the first department of biomechanics within a podiatric medical school - at California College of Podiatric Medicine in San Francisco. Over the years, podiatrists and other foot specialists have developed a better understanding of the basic principles of biomechanics resulting in a much more effective methods for treating the foot. Many ankle, shin, knee, hip and back complaints are caused or can be traced to abnormal mechanical forces in the foot. Numerous specialists have learned to use orthotic devices to control these forces causing the orthotic and shoe insert markets to expand dramatically.

Bi

ometrix-Ammon

was incorporated in January, 1985 for the purpose of significantly enhancing the methods used to produce a high quality customized orthotic device through the use of imaging technology and other sophisticated automation technology. The principals, Mr. Donald O. Flake and Dr. Merton L. Root together had more than 50 years experience in the foot care profession. Mr. Flake is himself an accomplished orthotic technician who had practiced his craft since 1973 in his own orthotic laboratory before forming an orthotic materials and supplies company. As a team, Mr. Flake and Dr. Root had succeeded in creating a revolutionary new technique for applying biomechanical corrections through a new computerized technique which produces consistently accurate orthotic devices. Biometrix-Ammon was a California corporation. In June 1986 an Arizona corporation was filed under the name Ammon Corporation in order to do business more efficiently from their headquarters in Mesa, Arizona.

Biometrix-Ammon commissioned a research study at Brigham Young University to conduct quality control tests on the production of orthotic devices at several major national laboratories. The study compared the consistency of each labs product with that of the product made with the use of the Ammon automated production system. It was not surprising to learn that the automation system was substantially more consistent than its human counterparts. However, it was a surprise to find that the lack of consistency varied not only from lab to lab but also from within the same lab - when identical impressions were sent to the same laboratory with the identical prescriptions, the results were far from identical! Reference article: "A Comparison of Automated versus Manual Techniques in the Manufacture of Orthotics", by Kellen S. Wilkes, April 1988.

Mr. Flake was business-oriented and Dr. Root was medicine-oriented. For orthotic manufacturing automation, engineers are definitely needed. As a software engineer, I joined Ammon Corporation in early 1990. Mr. Flake was the boss and I was the one and only engineer at the time. My main job was programming, but I also needed to maintain the scanners. Besides hiring an engineer, Ammon contracted a large technical company named Wayko Corporation to make scanners. An article in Podiatry Products magazine described the product (refer to 'Reference Figure 1' at the end of this page). Wayko's scanners utilized the shifting of the laser interference pattern generated from helium-neon (HeNe) laser. Besides the foot scanner shown in the article, there was the lab model which was very large. I felt these scanners were way too big and complicated, so I made my own design later on.

Ammon struggled financially and withdrew from the field soon after. I was transferred to Ammon's partner in Arizona and stayed there briefly. Then I was invited by a CNC milling machine company in Silicon Valley in California. My job title was software engineer. My background of working in a CNC company helped me in my future business. Encouraged by the idea that Mr. Flake had, I quit the CNC job, and started my own company, Sharp Shape, in early 1993. I thought there should be a market place for orthotic manufacturing automation and I should be able to do it. It has been proven to be true. It also proved that the job was tough.

Fa

cing the challenges:

Orthotic automation contains three main parts, i.e. the digitizer, the CAD/CAM software, and the miller (milling machine). To begin the process of building a pair of orthotic devices, an accurate measurement must be taken of the feet. The most widely used method of taking impressions of the feet at that time was plaster casting. Plaster casting is messy, inaccurate if not done properly, and time consuming. To manufacture the orthotics manually, pouring the plaster slurry, building the plaster cast and thermo-forming the plastic also involve messy, time-consuming and labor-consuming procedures. Mr. Flake, an entrepreneur, had the sharp vision and found this market direction. However, big funding was needed and the project was too big to handle.

A digital device can be used in measuring feet to replace plaster. At the time, ADT's digitizer was a wand-style (stylus) device and Amfit's digitizer was a pin-style apparatus. Each of them had merit, but they all had disadvantage compared with an optical device. There was a company called Cyberware. They used laser to make their scanners, which are not only used in orthotics, but also in generic fields. In 1990s, I reached Mr. Stephen Addleman, VP in the company and he sent me a 3D sample file, which was a person's face, which impressed me a lot. Instead of using laser interference pattern like Wayko did, Cyberware engineers spin the laser dot into a laser line, and move the line up and down to scan objects. Then they use a CCD camera to pickup the laser curve to calculation the geometry of the object. Their earlier models used the HeNe laser also. I felt there were some merits in their scanners. So Sharp Shape used laser. Instead of using a HeNe laser, we used a laser-diode, which has much less energy, but has very small size. The trend of using laser-diode has continued today.

The CAD/CAM software used in the orthotic automation was premature at the time. I am familiar with the software used in Ammon. One things was for sure: there were no standards in terms of cast correction types, milling interfacing, file format, etc. Customers needed more.

The CNC milling machine is an off-the-shell product, but the initial companies chose either to make (Amfit) or to carry (ADT) a CNC machine in their automation package. The advantage was to increase the value of their systems. But the disadvantage is that servicing the CNC is a complicated job and it is hard to sustain. Sharp Shape chose not to make or carry the CNC machines.

Mr.

Michael Grumbine

was the owner of ADT (American Digital Technology) in late 1980s and early 1990s and he held a patent which is related to the orthotic manufacturing automation. The US patent number is 5054148. ADT had around 10 orthotic labs as their clients at the time. ADT systems mainly produced direct-milled polypro orthotics. ADT charged royalties from their systems. Some lab owners and technicians talked a lot about the ADT patent. Some said that ADT's patent covers orthotic milling with certain tool path patterns. As long as you do not mill the orthotic vertically (or in helix pattern), you do not infringe their patent. The persons I met did not know exactly what the patent covered, but they all are afraid of patent infringement.

For their orthotic systems, ADT hired some brilliant engineers, such as Mr. Michael P. Kriechbaum, Mr. Joe Jared, and Mr. Dennis Fletcher. By only relying on the patent without these hard working employees, ADT orthotic systems could not make sales as good as they did.

I met Mr. Grumbine in a show in the mid 1990's. I approached Mr. Grumbine and introduced myself. In my heart, I was a bit afraid because I was not sure what he would say about their patent. Mr. Grumbine was kind and we chatted a little bit. I was surprised that he did not say a word about the patent. As I know, ADT never sued anyone for patent infringement. But the existence of the patent did give ADT the edge of advancing itself in the orthotic market.

Mr.

Tony G. Tadin

worked as a Chief Executive Officer & Founder at Amfit for many years. Amfit has a long history. It was established in 1977. I am not sure what it did initially. At the early 1990's, Amfit made and provided miller to Amfit system. As far as I know, making a miller for such a business is very unique. Sharp Shape did not choose to make a miller and we leave the work for a professional CNC company. Amfit system produces EVA insoles at the time. Some of the Sharp Shape customers came from Amfit users. Amfit sells the EVA blanks with different durometers. Because the cost on blanks are a burden, some of the users chose to use Sharp Shape systems. Besides, some labs did not like EVA as the orthotic material needed by podiatrists. The influence of Amfit is far-reaching.

In the 1990s, I received a letter from an Amfit attorney. It is a kind reminder that Amfit had patents covering the field and asked me to be aware of possible infringement. One of the patent numbers is 5689446 (Foot contour digitizer). I was committed to the idea of using laser to create our digitizer, so I did not feel we have infringement issue.

Dr.

John Bergmann

is a podiatrist. He was the owner of Bergmann Orthotic Laboratory. Bergmann Lab is another company which invested a lot of money in the orthotic automation. My former boss Mr. Flake told me that Mr. David Parker, an software engineer, used to work for him, but later worked for Dr. Bergmann. Bergmann Lab advertised their foot scanner frequently. Their scanner looked very much like the Cyberware scanner, so I believe they must have a deal with Cyberware. My impression of Bergmann Lab was that they were successful and they had a lot of funds. Their ads often appeared on the cover pages of a magazine, compared with Sharp Shape's infrequent ads which appeared as quarter or half page.

Equally important but less publicly known is Dr. Michael Burns, DPM. Dr. Burns was the owner of Burns Lab in McCook, Nebraska. Burns Lab invested a great deal of money in Ammon's system in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Because the technology was not mature, they failed to get what they invested. I felt really sorry for them. That was why Burns Lab was the first client of Sharp Shape. Ms. Marry Thorson, the life-time manager for Burns Lab was my first contact on our client list. Because the setup was Sharp Shape's first system, I went to McCook three times for it and the first setup trip lasted 2 months and I rented an apartment there. For the second trip, I drove to McCook from California. It reminds me the song 'Take me home, country roads...'

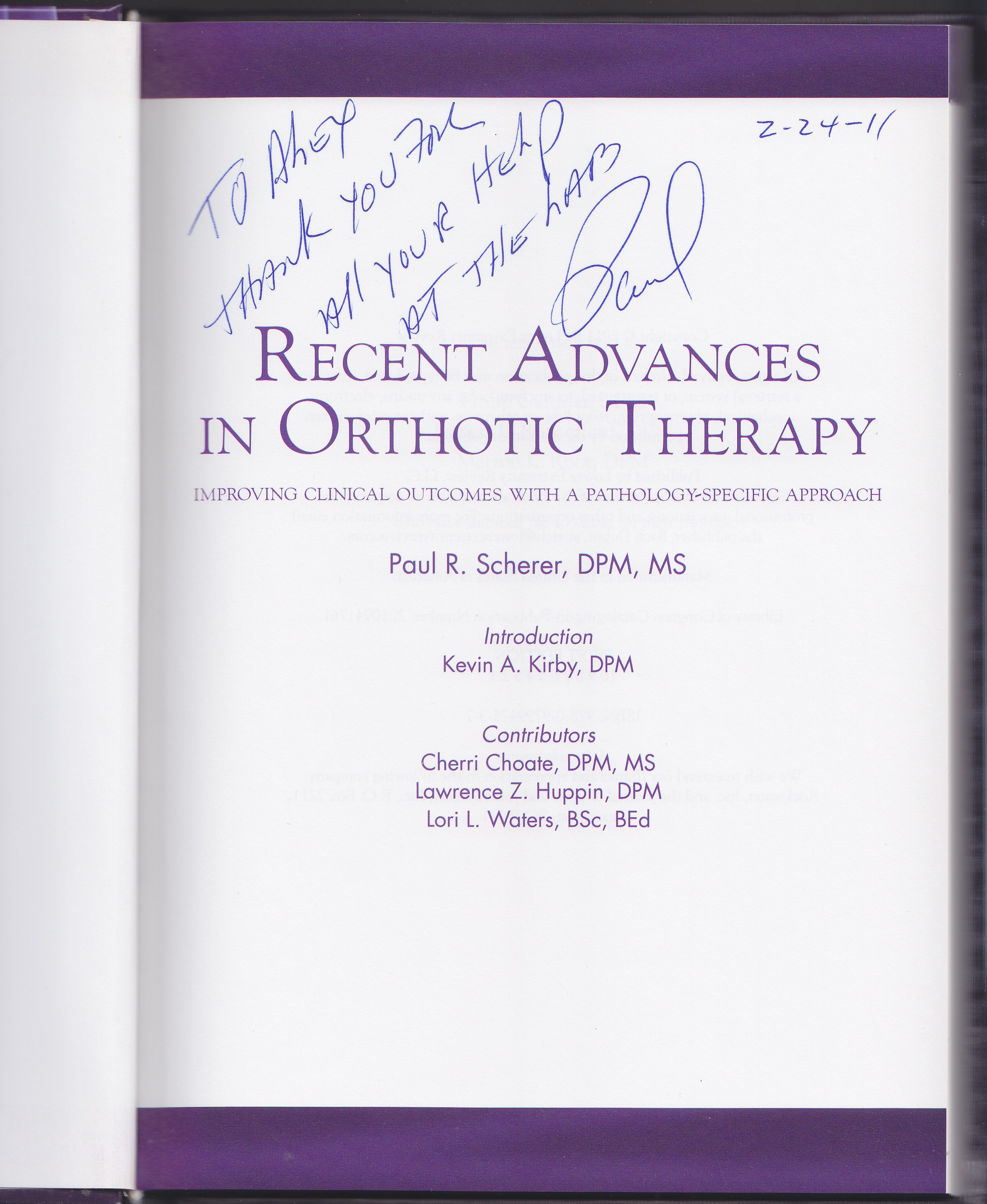

Another equally important and well known figure was Dr. Paul R. Scherer, DPM. Dr. Scherer was one of the early podiatrists who successfully applied the CAM/CAM technology to the field of foot orthotics. Dr. Scherer and his partner, Mr. Tom Alley in ProLab, started to contact me when I was in Arizona. They were interested in an orthotic production system. After Sharp Shape started, Dr. Scherer shed lights on my work regarding how the automation system should solve the podiatric problems. He explained to me about forefoot varus and valgus etc and how they should be presented in the software. Dr. Scherer gave me his book 'Recent Advances in Orthotic Therapy' (refer to 'Reference Figure 2' at the end of this page) as a gift. Dr. Scherer's pass away was a shocking news. ProLab became Sharp Shape's second client.

Sh

arp Shape

was created in the beginning of 1993. At that time, ADT already had at least a hand full of automation systems running. Amfit had more systems than that. I did not dream we could some day catch up with them. I noticed ADT sold the CNC machines in their systems and they also charged royalties from their systems. The cost was too high for some labs. ADT systems mainly produce direct-milled polypro orthotics. By studying their business model, I figured that we need to make some changes.

Sharp Shape's systems mainly produce wood molds. Using MDF (Medium Density Fiberboard) to produce corrected foot molds across the USA was Sharp Shape's greatest contribution. Making wood mold is not because our limited system capability, it is because of customers' choices. Our systems can produce wood molds, polypro orthotics and EVA insoles. However, wood molds allow users to use a variety of materials, such as polypro, subortholen, EVA, and graphite to make orthotics. Sharp Shape finally set up more than 80 orthotic automation systems world wide. Since we do not charge royalties, our income was not significant. However, the achievement feeling of millions and millions of people wearing the orthotics produced from Sharp Shape's systems is sensational.

Because I set up systems onsite, I visited many labs and met many lab owners and technicians. Although lab owners come from all walks of life, they mainly come from a related field such as podiatry or a shoe repair shop. Each of them is my tutor. Mr. Barry Sokol, former owner of Solo Lab, gave me a book titled "Business By The Book", Larry Burkett, 1990, as a gift. I asked Barry why you chose Sharp Shape system, not other systems? One of his reasons was that you do not smoke and you are married. That was something surprising and unforgettable. In fact, I quarreled with my wife a lot, which might lead to a divorce at any time.

Besides, many labs invested in the orthotic manufacturing automation. They contribute to the fact that orthotic manufacturing automation finally prevail today. Right now, almost all labs have some kinds of automation systems. Many lab owners and lab managers and employees treated me as a professional and sometimes as a friend. They include but are not limited to Ms. Ethel Ewing, Mr. Jack Kaufer, Mr. Jeff Root, and on and on.

Needless to say that there were also hard times for a developer who is involved in the orthotic manufacturing automation field. There are physical and mental challenges. For example, I had booked the airline ticket, but I had health issue at the time of boarding. To cancel or to continue was a hard decision to make.

To

summarize:

"The three most important people are Michael Grumbine of American Digital Technology, Tony Tadin of Amfit, and John Bergmann, DPM, of Bergmann Orthotic. These are the medical technology entrepreneurs who pioneered the software, adapted the hardware, and created the networks. A fourth and less known figure is Alex Shang, Ph.D. of Sharp Shape. What these four people do commercially and technologically affects the entire field." By Edwin Black, Biomechanics, November-December, 1994, page 79.

Looking back at the technology developments happened in the orthotic manufacturing field, I witnessed some big changes. The first Wayko cast scanner had a gigantic size and it was mounted on the celling to scan a foot cast on the floor. Our current iPhone scanner is hand-held. The scanning speed and accuracy are both superior than the old scanner's. However, we should not laugh at the old technologies, because our current achievement is built on top of the previous technologies.

Sp

ecial Note:

This article reflects my own opinion and it may not be inclusive. I will keep updating this page. Please email me if you have any comments. Email: info@aoms.me

Re

ference:

Below are some photos of the history.